Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Essays & Editorials Student Essays A brief narrative on the 2006-09 essays by Matthew Feldman 2008 - 2009 2007 - 2008 2006 - 2007 H.E.A.R.T Editorials | ||||||||||||

[Please note that editorials posted in this section are the sole viewpoints of the individual author and do not necessarily

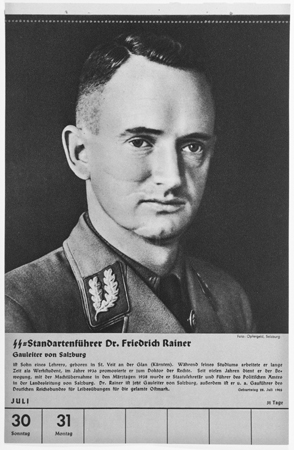

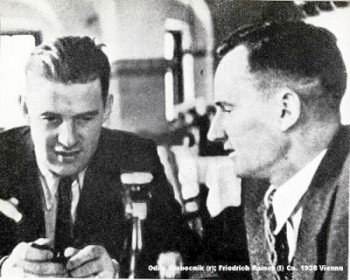

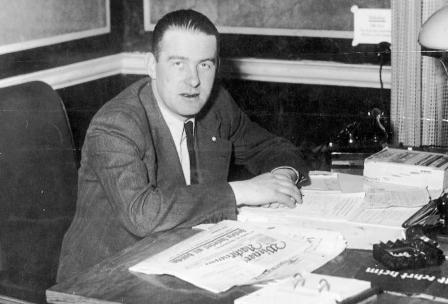

Friedrich Rainer and Odilo Globocnik Typical Nazis, an Unusual Friendship, & Sinister Roles [Photos added to enhance the text]

They met sometime in 1933. They worked together and became friends they stayed together until the Gotterdamerung when death finally separated them. When one committed suicide with his cyanide capsule, the other stepped over his body and marched off to prison and eventual execution.

They were typical Austrian Nazis, but their lasting friendship made them unusual in Hitler’s fiefdom, their concern for German purity was their common bond.

Friedrich Rainer and Odilo Globocnik are important for any number of reasons, their story affirms the major, and not infrequently, sinister role Austro- Nazis played in the Third Reich, especially in East and South East Europe. They were part of the Austrian contingent who scattered throughout the Reich and its conquests and did the Fuhrer’s bidding.

Their story also depicts two images commonly associated with the National Socialists. Rainer was intelligent, well educated, articulate, capable and principled. He was able to make the transition from the streets to government.

He fits a pattern much like fellow Austrians Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Arthur Seyss- Inquart or colleague Josef Burckel from the Saar. Globocnik, on the other hand, was a bully, an opportunist, a fawner, a bureaucratic mass murderer surrounded by corruption, and incapable of changing the streets for public office. He was more akin to the Brown Shirt thugs who fought for the Party and did the bidding of the masters, but had no ability for independent leadership.

Further, the lives of the two men exemplify the importance and intensity of the Grenzland Nazis. Those who were raised and lived on the borders of cultural Germany were frequently the most devoted and active nationalists. Like Hitler, Kaltenbrunner, or Konrad Henlein in the Sudetenland, they came from an environment of fear where non-Germans had challenged the traditional Germanic hegemony. They devoted their lives, therefore, to protecting, if not extending, that hegemony.

Finally, while solid work has been done on the pre and post Anschluss careers of the two men and on Globocnik’s notorious activities in Poland, little has appeared on Rainer, his friendship with Globocnik, or their co-operation in Trieste during the last years of the war.

Colleagues and fast friends, the two had much in common. They were born into middle class families on the fringes of cultural Germany. They worried about race, were ambitious, and played active parts in the illegal Austrian Nazi Party. As early members of the SS, they collaborated as lieutenants of Hubert Klausner, the captain of the Carinthian Nazis. They climbed the Party ranks to positions of national prominence, becoming Gauleiter in the post-Anschluss Austria. And they served as key members of the Hitler hierarchy in the occupied lands, Globocnik in Poland and Rainer in Slovenia and Italy.

Yet their differences were significant. Rainer was a thinker; Globocnik, a worker. The first was able and intelligent while the other was average and frequently incompetent. One was principled; the other, opportunistic. One was confident while his friend was uncertain, always scrambling. Rainer easily made the transition to official power; Globocnik could not break the pattern of free-wheeling illegality. The former eventually becomes the protector; the latter the protected. And if it mattered, one was Protestant while the other was Catholic.

The more capable Friedrich Rainer (Friedl) Rainer was first and foremost a Carinthian, born to a middle class family on 28 July 1903 in St. Veit an der Glan, he traced his regional lineage back several centuries.

He followed the usual educational route for the middle class, eventually graduating in 1926 with a Doctorate in Law from Graz. A great sports enthusiast, especially as an active gymnast and an avid skier, he joined one of the duelling fraternities at university, acquiring a scar on his left cheek, which along with his blonde hair, fair skin, blue eyes and medium frame gave him the German – Aryan look.

Rainer was a pronounced nationalist from his youngest days and an early supporter of National Socialism. At sixteen he worked to protect Carinthia from the Slavic threat to the south; at twenty he joined one of the first Brown Shirt (SA) groups.

After 1930 his Party activity intensified, he served on the local executive, became head of the Nazi sports union for Carinthia, began working with Gauleiter Hubert Klausner, joined the SS, and took over the provincial news service (i.e. gathering intelligence).

But his big opportunity came following the failed July 1934 putsch. Klausner asked Rainer to help rebuild the shattered party organisation in Carinthia. For the next months, as one of two deputies, Rainer played a key role with the Gau news service, press, propaganda and training. The other deputy, his new colleague was Odilo Globocnik.

While Rainer came from the border of the German Reich, Globocnik was form the fringe of the German – Austrian sphere. Born in Trieste on 21 April 1904, his father was a retired cavalry officer and a senior postal official. The paternal family was professional and middle class while the maternal side came from generations of farmers.

The family name was originally Globotschnig, but in 1825 a priest had Slovanised it to Globocnik. The family, however, spoke German as the mother tongue. The young Globocnik was also conversant in Italian, a by-product of growing up in Trieste.

Globocnik was originally educated to follow his father into the military, after attending elementary school in Trieste, he was sent in 1915 to a military school in Lower Austria.

The collapse of the Hapsburg Empire, however, forced the young Globocnik to enter a technical and vocational institute in Carinthia, and resulted in his acquisition of Austrian citizenship. In 1923 he began employment with an electrical firm, and then moved on to heavy construction, always working in the Klagenfurt region. By 1933 he had become a Diploma Engineer. But his construction career soon ended because of his political activities.

Like Rainer, Globocnik began his nationalistic and political career early, as a teenager he participated in the defence of Carinthia against Yugoslavia and was awarded the Carinthian Cross for Bravery. In 1920 he worked with the local paramilitaries in the plebiscite campaign to keep his province in Austria and out of Yugoslavia. Then two years later he joined the Austrian Nazi Party and helped organise Carinthian SA units.

Again, like Rainer, his Party involvement increased after 1930, especially when the Carinthian organisation acquired a definitive form. He served first as a propaganda functionary, then as head of the provincial propaganda office, and in 1933 became Deputy Gauleiter. As a courier for the Party and the SS, he made frequent and secret trips to Munich, since he was one of the chief Austrian liaison with Nazi Germany he met leading officials of the Reich.

For the unemployed Globocnik, restless and ambitious, the NSDAP gave him a purpose, it also gave him a new colleague, in the aftermath of the failed July putsch, Globocnik came to share his role as Deputy Gauleiter with Friedrich Rainer. The two men soon became collaborators, confederates and co-conspirators – and then friends.

During the following four years, the two men worked closely together, the internal confusion of the Austrian Nazis allowed Rainer and Globocnik (with their mentor Klausner) to play influential roles in Party circles.

The numerous arrests and imprisonments (including their own for a few months) meant the Party was desperate for leaders. Rainer and Globocnik became chief functionaries in the national hierarchy. From here they developed a close relationship with Arthur Seyss- Inquart, a lawyer with close connection to the Austrian government and a warm sympathizer of the “German” cause.

In the summer of 1936 the two young men met Hitler who seemingly gave approval to their approach to indigenous Party affairs. In March 1938 the two played key roles in the Anschluss. From their centre in Vienna, Rainer issued the orders to SS, SA and Party units, while his friend by telephone, became the main conduit of information to and from the Reich. As a finale the two met Heinrich Himmler at the airport when the Reichsfuhrer became the first German official to arrive in Vienna.

While the two friends played bold and prominent parts in the transfer of power to Seyss-Inquart they did not participate in the actual absorption of Austria by Germany. Like other local Nazis, they had welcomed the threat of a German invasion to intimidate the Austrian government into permitting a peaceful, indigenous Nazi takeover.

But a German invasion was another matter, like many fellow Nazis they were disappointed by the immediate turn of events in March. They did get their rewards however at the end of May Hitler appointed them to be Gauleiter in the new Party hierarchy for Austria.

They received SS promotions, offices in the new government and seats in the Reichstag. Rainer also added to his honours various posts in the Party’s sports, youth and physical education units. These honours and the new posts, especially as Gauleiter marked personal high points for the two friends.

They were further honoured since both were held in high esteem by their comrades; a well placed Reich official observed that Rainer made an extraordinarily good impression. He was quiet, yet had an inner passion; he was intelligent with a grasp of the whole picture; he enjoyed great authority and was obviously the deciding personality near Seyss-Inquart.

Rainer was also considered well bred and absolutely reliable he would always follow the Party line. Edmund Glaise-Horstenau, a prominent Austrian politician with German sympathies and a later colleague, commented that Rainer was a fine young man, almost boy-like in his appearance, and was a good public speaker.

Other colleagues referred to him as the “foreign minister” of the Gau Carinthia, quite diplomatic in his approach to people. With these traits and especially with his background, he fits nicely into that group whom Jonathan Petropolous has recently called, “Nazi leaders who were raised to appreciate and promote the high European culture that flourished throughout Europe prior to 1914.”

The view of Globocnik, while positive, was somewhat different, he was seen as an unusually hard, strong willed idealist who had good organisational and propaganda experience. But some felt he was not ready for important leadership positions since he needed more pertinent experience, perhaps as Deputy Gauleiter somewhere or as an official on the staff of the Deputy Fuhrer.

Globocnik needed to know more about the central policy of the Party. His work during the illegal period had been worthwhile and he was one of the best liaison people, but organisational concerns would be crucial during the months after Anschluss and Globocnik was not viewed as ready for that.

As his friend Rainer wrote, “That Globus (Globocnik) is a representative of Blood and Soil with aggressive personal methods is a fact. That he usually does not weigh his words carefully is likewise a fact.” Klausner described him as having a “boyish freshness with a farmer’s cunning.”

The two young men, like others in their circle, had clearly become successes; they had worked their way up the Party hierarchy and before the Anschluss had formulated key policies. They had played crucial roles in the union of the two countries – and their efforts had been recognised. All the same, now their careers began to diverge, one failed while the other succeeded.

At first, Globocnik the new Gauleiter of Vienna, appeared to be the man of the hour. Despite some reservations, he had the support of Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich as well as Klausner. Josef Burckel, Hitler’s deputy for Austria, praised him as “having the proper credentials.”

But he soon showed himself to be pompous, impulsive, overbearing, a braggart, a poor judge of character, an inefficient negotiator, and an ineffective speaker. Further, as a Carinthian, he lacked supporters in Vienna.

He began to stumble from one problem to the next, he erred in his approach to anti-Semitism, the Church, currency and finances, and the confiscation of property, and he found himself in trouble with other forceful Nazi personalities in Vienna.

His weakness particularly showed when he could not gain control of the local Party. As the British Consul-General wrote: “Off the seven Gauleiter appointed Herr Rainer in Salzburg is generally considered to be the best, Herr Odilo Globocnik, Gauleiter of Vienna, proved the worst choice which could possibly have been made.”

In the end, despite the efforts of his friend Rainer who tried to intervene on his behalf, Hitler removed Globocnik as Gauleiter. The announcement was terse, on 30 January 1939 the Fuhrer announced in the press, “I have accepted the request of Party Member Odilo Globocnik to be relieved of his office as Gau leader of the Gau Vienna.” He then named Burckel to replace him.

Rainer on the other hand, had a much easier time in Salzburg, the Salzburg Gau was the smallest of the Reich’s forty Gau, there were neither major splits nor divisions within the local Party, and there were no other personalities competing for power. Party and governmental duties were united since Rainer served also as provincial chief. There were no significant minorities or hostile groups such as socialists or Marxist workers and Jews. Finally the Gau was relatively homogonous.

Salzburg had symbolic importance because it was directly in the sight of the Fuhrer’s mountain retreat, the “Eagle’s Nest” at Obersalzburg. Those who worked “in Salzburg under the eyes of the Fuhrer ”felt that theirs was the “Fuhrergau,” in addition Salzburg had long been an important historical and political centre in Germanic history. Its role as the “German Rome” was undisputed. After the Anschluss it became headquarters for the important Military District of Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia, Tirol and Voralberg. Rainer may have moved to a small Gau, but it held a crucial position in the Hitler hierarchy.

Unlike Globocnik in Vienna, Rainer brought Gau Salzburg into line, transforming the Party quickly from an illegal to a legal organisation, while working well with subordinates. He kept his peace with Burckel and the others and maintained close liaison with the authorities in “Old Germany.”

He “Aryanised” the civil service and “cleansed” local businesses of Jews, he eliminated the unemployment problem within months, thanks to German re-armament and the attendant military activities. He launched a major campaign to promote Salzburg as the prime cultural and intellectual centre of the new Reich.

Since the city had long been identified with music and the Baroque, Rainer attempted to make it the city of music and learned activities; he established an office for artistic and cultural affairs. He demanded the return of artwork which had been moved to Vienna, when Salzburg had been secularised in the 19th century.

In a manner similar to his colleagues Baldur von Schirach, Hans Frank, or Robert Ley, he turned his official seat at Chiemseehof into a showpiece filled with art work and furnishings from the confiscated property of Jews.

Further, with the assistance of Himmler he planned an SS university in Salzburg, the first step of which was the establishment of an institute dealing with ancestral inheritance. In the summer of 1939 Rainer launched the Salzburg Academic Week for the rectors of all German universities. He proudly wrote in the programme that for the first time since the acquisition of Nazi power, German scholars were united in Salzburg under National Socialist leadership.

Rainer also worked with Seyss-Inquart and Glaise- Horstenau to establish a library and archives dealing with military scholarship. This project, like the Academic Week, lapsed only with the outbreak of war.

Rainer’s major activity, however, was his attack on the Catholic Church, which soon identified him as the most rabid anti-cleric in old Austria. Shortly after assuming his duties he gave an interview to the Party newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter, in which he said he wanted to change the image of Salzburg from a clerical city to one which reflected National Socialism.

In the future Salzburg would be viewed as a centre for Nazi training and conditioning, before long Rainer closed Franciscan priories and Capuchin convents, converted the palace of the Archbishop into the headquarters of an SS unit, and appropriated buildings for government offices.

Further he issued warnings that he would punish all disturbances of “religious peace.” The attacks on the church, the only organisation which could have seriously challenged the Nazis, continued for the duration of his time in Salzburg.

Unlike his friend Globocnik, Rainer’s work was seen by his superiors as a success and he received numerous rewards for his efforts. In July 1938, he was promoted to SS-Senior Colonel. Six months later he became a SS- Brigadier General and Hitler awarded him the Golden Badge of the NSDAP. In June 1939, he received a Party citation for his “service to the German people.”

His administrative abilities were recognised in September when he was appointed Reich Defence Commissioner for Military District XVIII. Then in the spring of 1940 when the Ostmark Law reorganised the earlier provinces of Austria into seven Reichsgaue, Rainer was named Governor of Salzburg.

But if he was successful, not so his friend, Globocnik’s career was in virtual ruins, he had to rely more and more upon his friends for protection and patronage. Himmler would become his greatest supporter professionally, but Rainer remained his best and most long standing champion, a friend who helped him sort out any number of troubles.

Globocnik’s love life was a noteable example of their relationship. In 1922 Globocnik had become engaged to Margareta Michner who was then fourteen years old. But the affair had never progressed beyond the betrothal. In late 1939, when Globocnik finally tried to break the engagement, her father, Lieutenant Colonel Emil Michner, wrote to Rudolf Hess, pointing out how his daughter had been “dishonoured” by Globocnik.

Hess sent the matter to Himmler who contacted Rainer, it took Rainer several weeks, a number of letters, a special trip to visit the girl and her father, the mention of Himmler’s interest, and an appeal to “nation, folk and race,” but he persuaded Michner and his daughter to drop the matter – and the “engagement.”

This episode showed that Globocnik had not only a friend who would go the extra distance to help him, but a colleague, Himmler, who would intervene on his behalf. It was Himmler who now played the key role in reviving his career. The Reichsfuhrer had resuscitated Globocnik after his January 1939 humiliation. Two days after his dismissal as Vienna’s Gauleiter, Himmler appointed Globocnik to his Personal Staff. There he underwent three months military training and was briefly assigned to an Armed SS unit during the Polish invasion.

These tasks were only temporary, however, Himmler had other plans for him, on the 1 November the Reichsfuhrer named Globocnik as the SS and Police Leader (SSPF) in the Lublin district of old Poland; hence he became the highest SS authority in that region. Issues of race, economic production, ethnic collusion and German resettlements became Globocnik’s new foci. Apparently he was to be no ordinary SS and Police Leader. His first project turned the Lublin district into a huge Jewish “holding area.”

Between December 1939 and February 1940, tens of thousands of Jews were deported to this region from all over the Third Reich. Globocnik supervised their settlement and employment. He made the district a centre of SS economic activity. He also played a key role in establishing the local Selbstschutz, self –defence units of indigenous ethnic Germans, organising them shortly after he arrived, he used them as auxiliary police to deal with Polish and Jewish labour and the distribution of confiscated property.

Further he directed resettlement schemes, in the south-east portion of his district he discovered evidence of earlier German communities, the find prompted him to plan a re-settlement programme in which the Polish population would be deported and ethnic Germans would be relocated.

His most notorious assignment, however, came in the spring of 1942 when Himmler appointed him head of Aktion Reinhard, the campaign that exterminated hundreds of thousands of Jews. Reporting directly to Himmler, Globocnik planned the deportations; built the death camps, co-ordinated the transfer of Jews from different regions, killed the victims, seized their valuables, and transferred confiscated property to the appropriate authorities in the Reich.

The death camps he administered at Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka could daily despatch 60,000 people, later he added the camps of Trawniki and Majdanek, he had a terrifying assignment.

But Globocnik was clear about his objectives and proud of his work. He wanted to make the Lublin district the first purely German district in old Poland. The action against the Jews should be carried out with all deliberate speed, he told one of his colleagues, “in order to avoid getting stuck in the middle one of these days when some sort of difficulty may force us to stop.”

He took a great interest in the various aspects of “his camps” especially the gas chambers, once when questioned about the buried corpses – wouldn’t cremation be better since others might judge events differently – Globbocnik replied:

“Gentlemen, if there were ever, after us, a generation so cowardly and so soft that they could not understand our work which is so good, so necessary, then, gentlemen all of National Socialism will have been in vain. We ought, on the contrary, to bury bronze tablets stating that it was we who had the courage to carry out this gigantic task.”

The pace of genocide was so intense that by the spring of 1943 most of Globocnik’s heinous extermination work ended. Some 1,650,000 Jews had died under his direction. At this point Himmler decided that Auschwitz- Birkenau, with its larger gas chambers and crematoria, could complete the job.

Himmler, however, had not finished with Globocnik, he re-assigned him an economic task, in March 1943 Globocnik became the operational chief of the Ostindustrie (OSTI) where he exploited Jewish labour for the SS munitions factories in the General Government and acquired and sold the personal property of the Jews. At his peak he directed 18 different work places using 52,000 workers.

Globocnik was obviously busy, but not necessarily successful, according to numerous Nazi sources his re-settlement schemes led to complete chaos. The forced evacuation of Poles resulted in increased sabotage while the partisan movement grew until it became a major worry for the occupying Germans.

Rudolf Hoess, the commandant of Auschwitz, especially criticised Globocnik for major mistakes. “I had to have a serious talk with him about the machines and tools sent to us from the local arms factory. These machines were the worst junk…. he gave orders and directives which ran the exact opposite of those issued by the Inspector of Concentration Camps.” Hoess concluded that “Globocnik was a pompous ass who only understood how to make himself look good.”

The most damaging crisis for Globocnik came in 1943 over his differences with the new governor of Lublin, Richard Wendler, a brother-in-law of Himmler. According to Wendler, Globocnik and his men ignored directives and went ahead with projects without considering the civilian government. Wendler concluded that it was impossible to work with him.

“Please dear Heinrich change him.” Himmler however, did not abandon Globocnik, instead he planned other tasks further to the East. Before, a transfer could take place, however, Italy collapsed and Globocnik was given a new assignment in the city of his birth, working with his old friend Rainer.

While Globocnik’s time in Lublin did not end well for him he had established a grisly record unequalled by many others in the Nazi hierarchy, as head of Aktion Reinhard he bore general responsibility for the death of some 1.7 million people. He had enriched the Reich with the personal property of the deceased to a value of nearly 180,000,000 RM. Few could match these ghastly achievements.

His friend Rainer, however, had surpassed him in rank, in the late summer of 1941 Berlin had appointed Rainer Gauleiter and Reichskommissar of Carinthia. Here he directed both the Party and the government. He also became Chief of the Civil Administration in the Occupied Territories of Carinthia and Carniola. He was heralded as the best appointment Hitler could have made.

Rainer’s work in the south had similarities to his friend’s in the east, he too dealt with questions of racial purity, it began with his installation as Gauleiter. In November 1941 – in the presence of honoured guest Odilo Globocnik – Rainer was given his direction by Robert Ley, the Reich Organisation Leader.

After complimenting him, Ley established the “Germanic” tone, he spoke of Carinthia’s thousand year role as protector of the Germans, pointing out that Carinthia was a a border Gau, and emphasising that on the frontier of the Reich one found the heart of the nation. Rainer responded by promising that he would lead the Gau in the “old Carinthian tradition,” a tradition which was purely German. He also affirmed that he had a second complementary task, the Fuhrer had instructed him to make the newly returned lands of south Carinthia and Carniola once again pure German. This Germanisation theme was repeated two weeks later when the Reich Interior Minister, Wilhelm Frick, installed Rainer as Reichkommissar, Frick too complimented him, noting his good work in Salzburg. But the task in Carinthia was different, “Your principal task will be to include in the German Reich the entire new areas of Southeast Carinthia and Upper Carinola, making it a worthwhile part of your Gau…. Your task Party Member Rainer, is to make this district entirely German again.”

Rainer responded, as he had earlier replied to Ley, but this time took a tougher approach. He told the people of the occupied territories that if they worked with him they would receive the protection of the German Reich. Those who did not, the partisans who murdered and robbed, and those who helped them would die.

With these speeches, the “Carinthian Question” and the other final solution became public. And here was the on-going link with Globocnik, one friend dealt with the final solution of the Jews in the East, the other dealt with the Slovenes.

But instead of trying to eliminate them, Rainer attempted to re-make them into Germans. He sought to exterminate a culture by encouraging the residents to find their German roots. For him, as for many German Carinthians the chief cultural enemy was not the Jew, but the Slovene. Germans had competed with Slovenes in southern Carinthia, Styria and Carniola for centuries. Since the two peoples had struggled for so long, anti-Slovenism had a much greater appeal than anti-Semitism.

To help in his new work Rainer had a useful tool, Germans of the region had developed a theory that southern Carinthia, Carniola and Southern Styria were peopled by three groups, not two: Germans, Slovenes and the Windisch.

Germans and Slovenes were nationally minded, but the Windisch lay in between, although they spoke the Slovene language, they were supposedly bound to Germans in their way of life, culture and sentiments. The Windisch in essence, were those inhabitants who spoke Slovene but wanted to be German. This theory pre-dated National Socialism and Friedrich Rainer, and it possibly helps explain why the National Socialists did not adopt an intense extermination policy toward the Slovenes as they did toward the Jews.

When Rainer assumed responsibility for Germanising the South, he discovered that the local residents were not particularly receptive to his efforts. Many Slovenes joined the partisan movement and supported forceful opposition.

Thus Rainer had to deal also with questions of law and order, when he made his first trip south to Veldes in December, he spoke about the future generation of Germans, but he also spoke about the need to stop the “bandits.” He promised that National Socialists were ready to deal with any enemy. Later in Krainburg when he received a Slovene delegation, he reminded them he was no “stranger in the land,” further he informed them that Hitler had ordered him to restore peace and order with the strongest measures necessary.

In his campaign to Germanise the Slovenes, Rainer accepted several projects, including deportation and a re-population of the area by ethnic Germans. Originally the Nazis had anticipated moving 250,000 nationally –minded Slovenes from the German occupied territories of Carniola and South Stryia to other parts of Europe.

In April 1942 Rainer’s administration decided to begin with some 50,000 inhabitants in Carniola, units of the SS , police and soldiers swept down on a number of Slovene villages, gave hundreds of people only a few minutes to gather their belongings, moved them to a holding camp near Klagenfurt, and then transferred them to the interior of Germany.

Other deportations followed, but never achieved the anticipated numbers because of wider war conditions and partisan activity. The goal, however, remained. Near the end of the war Rainer’s regime still talked about mass deportation.

Ominously, part of the plan called for the evacuation of the entire population of Carniola to Lublin, Globocnik’s old haunt. Rainer also supervised the second part of the scheme, repopulating the land. Nearly 6,000 hectares of confiscated land was turned over to German –speaking settlers from Italy’s Canale Valley in South Tyrol and others from Kocevsko, Bessarabia, Bukovina and parts of Germany. But since the Slovenes did not leave in the anticipated numbers this re-settlement scheme remained mostly unfulfilled.

In his approach to Germanisation Rainer aimed particularly at cultural extermination, he and his colleagues meant to destroy or prohibit everything that supported a Slovene national consciousness, including societies, organisations, literary endeavours and schools.

He made German compulsory in education, youth organisations, libraries and public places, signs everywhere, including apartment and house doors, demanded Carinthians speak German. Given and family names had to appear only in the German form. Those opposed to these orders were arrested, imprisoned, sent to concentration camps, tortured and sometimes shot. In the first year, 1942, 1217 Carinthian Slovenes were interned in German camps while twelve villages in the Gorenjska region were burned to the ground.

But the Germanisation campaign and the fight against the partisans in Carinthia and Carniola did not go well. In July 1943 the Volkermarkt Gendarmarie reported that the general situation in its region had worsened over the last six months. Partisan activity had increased, especially against people who were “German friendly.” The report concluded that the population was still 85 to 95 percent Slovene and was not giving up its language.

In September Rainer acknowledged the problem by offering an amnesty to all “Bolsheviks,” who through “error, seduction, or compulsion,” had joined the partisans. They could return home to live peacefully with their families without fear of punishment, but they had to abide by German law.

The campaign was also interrupted by the course of the war, the fall of Mussolini in September 1943 drastically altered the strategic situation for Germany, forcing Hitler to take control in Italy and its occupied territories. He created the two “operational zones” on the Northern Adriatic. One was the Alpenvorland under the Gauleiter of Tyrol. The other, the Adriatic Coastland, consisting of seven Italian and Slovene districts, was placed under the civilian direction of Friedrich Rainer, who now administered three areas: Carinthia, the occupied territories of Carinthia and Carniola and the new occupation zone.

In the new region Rainer was joined by his old friend, the day after his appointment Globocnik too received a new posting, instead of going to Russia as planned. Globocnik went to his native Trieste as Higher SS and Police Leader where he reported to Rainer as well as to the SS. The two friends had kept in close contact and had met frequently, Rainer had vacationed in Poland, but this occasion was the first time they had worked together for nearly four and one-half years. This time their collaboration would last until May 1945, when death finally separated them.

Globocnik arrived in Trieste at the end of September, setting up office in the Palazzo di Giustizia near Rainer’s local headquarters. For the next months both men were kept busy organising their respective new responsibilities. As in the past they worked well together; their close personal ties made it easier to pursue common goals. For his part Rainer, now called High Commissioner, tackled the administrative confusion of the Adriatic Coastland, beginning with Ljubljana, the most Slovene area, although his long range plan was to Germanise the region, he moved cautiously.

Deciding that the region must first have cultural and administrative autonomy, he approached local anti-Bolshevik, conservative circles and co-opted them for his plans. General Leon Rupnik, a Slovene, former officer in the Hapsburg army and Mayor of Ljubljana, became the new President of the region, while Dr Gregor Rozman, the powerful Archbishop of Ljubljana, became a key ally after Rainer promised to protect the Church and its property.

To gain their confidence Rainer assured them that he intended to eliminate Italian influence and re-create the old autonomous duchy of Krain. In the rest of the Adriatic Coastland Rainer made similar appointments. At the provincial level, he appointed as prefects native Italians who had never occupied government posts; as Mayors he named Italians, Slovenes, or Croats, depending on the local ethnicity. He gave the appearance that indigenous functionaries had considerable autonomy in their affairs, the reality, however, was quite different.

Rainer made the territory, nominally a part of Mussolini’s new republic, a de facto German protectorate in which he held the power. In accordance with Hitler’s direction he assigned German advisers and district officials, mainly Carinthians, to the provincial administration. As Rainer asserted, “Their function was to control the entire local administration.”

A prefect could not issue any proclamation without the approval of his German adviser while only the High Commissioner could issue laws, publish the official gazette, or hold judicial power. Rainer’s power became obvious, as did his link to Globocnik, when he established the “Extraordinary Court of Public Security.” He appointed its members and freed them from regular rules of penal procedure while Higher SS and Police Leader Globocnik controlled the prosecution.

No appeal was allowed from the Court’s decision although the High Commissioner could grant pardons. Rainer summed up his situation, “I controlled the Adriatic Coastland.” Having returned to the city of his birth, Globocnik worked alongside his friend as the chief SS official and policeman, his jurisdiction covered the entire Adriatic Coastland except for Ljubljana where Hitler decided the SS and Police from the other operational zone would have control.

Globocnik organised his staff to work in four areas: action against Jews, local defence forces, economic policing, and combating partisans. Later he added a fifth task when he became Rainer’s deputy in building a defence wall to protect the underbelly of the Reich. To help him he arranged the transfer of key personnel from his Lublin staff, including the SS “professionals” from Aktion Reinhard and some of the Ukrainians who had assisted them. He now re-organised them as Section R with three main branches in Trieste, Fiume and Udine.

Financing came from Rainer’s office, not surprisingly Section R became the Nazi’s key instrument in the “Jewish Question.” Globocnik also sent his representatives throughout the zone to establish German police authority. Most of these deputies as well as members of his immediate staff in Trieste came from Austria.

As would be expected, strong action against Jews began shortly after Globocnik’s arrival. The Italians had founded a Centre for the Study of the Jewish Problem but had not vigorously pursued local Jews. Section R now took over all available Italian records and established a small concentration camp at San Sabba, the old rice mill near Trieste.

It functioned primarily as a transit camp en-route to Auschwitz and other death camps, the first transport left for Auschwitz on 9 October 1943, by the end of the war some 20,000 Jews had passed through San Sabba, including 5000 who lived in Trieste. Although as many as 3,000 were executed there, the primary purpose was not as a death camp, as in Poland Jewish property was confiscated, then stored at San Sabba or deposited in a special bank account in Trieste.

Globocnik’s other responsibilities included the organisation and direction of local militia units, a task he inherited from Rainer. These auxiliary military forces, organised by ethnic groups to assist the local police in operations against partisans, included the Domobranci (Slovenes in Ljubljana and Croatians in Istria), the Stabswache in Trieste, and Italian fascist units.

Since they all wore different coloured uniforms, Rainer commented that “Globotschnigg had a very colourful military organisation:” to fight the Black Market, smuggling, inflation and price increases, he also built a 20,000 member Economic Police Force. But the task that absorbed most of his time, resources, and personnel was the struggle against the partisans: the Italians and the Titoist Slavs. It was “tough work,” Globocnik said.

He complained that the anti-partisan struggle was increasingly difficult, especially since he had such limited resources, his units suffered growing casualties and he had few replacements. The work, he observed, was more difficult than in Lublin and the success less. What Globocnik meant by “struggle against the partisans” was wide-spread reprisals and attacks against real and suspected supporters. These measures included attacks on the civilian population, shooting of hostages, and the destruction of homes and villages.

On some occasions Globocnik personally supervised the activities, an eyewitness explained how he presided at the destruction of Smarje village on 21 June 1944. “The population was first removed, in most brutal circumstances, from their homes which were then thoroughly looted and finally set on fire one by one. Altogether 151 dwelling houses were destroyed and several hundred persons were left without shelter, food, clothing and other every day necessities.”

Then in the summer of 1944, the two friends, collaborating as always, extended their activity. Hitler gave Rainer the responsibility of erecting a line of fortifications from Trieste and Fiume to the Alps. Rainer named Globocnik as his Deputy together they enrolled the people, mainly Italians, to do the work. The undertaking called Operation Poll was huge, Rainer claimed that some 4300 political officials and 120,000 workers were involved although other sources set the figure at 50,000. Whatever the number a defence line was built.

This project also provided Rainer an opportunity to reward his friend Globocnik, he recommended him in December 1944 for the German Cross in Silver. Rainer praised Globocnik’s extraordinary energy, great political skill and unique industriousness and his revolutionary National Socialist approach. In all his undertaking Rainer said Globocnik brought a performance which filled with wonder everyone who observed him. Hitler granted the award.

The close ties between the two men were also reinforced when Rainer served as the chief witness for Globocnik’s marriage in October 1944 and then hosted the wedding reception. Globocnik’s bride was the Carinthian leader of the League for German Maidens (BDM) about whom Rainer was very supportive, so much so that he facilitated in obtaining a “blessing” from Himmler.

But by late 1944 the Reich’s defeat approached, Rainer remained optimistic to the very end, but Globocnik took a more realistic view and sought to save himself. As late as 18 April 1945 Rainer told his political colleagues, “The situation is not hopeless. We still have a chance.” Globocnik meanwhile, acknowledged the obvious: “It was not a quarter to midnight, he said, but only a few seconds away.”

At the very end he fled North from Trieste, fighting a rear guard action, while seeking a hiding place in the Carinthian mountains. He left Trieste on 30 April and entered old Austria near Weissensee where he burned his last documents and took to the mountains north of the lake. Rainer also retreated to his native Carinthia, hoping to ensure that it would remain united. Rainer’s immediate goal was to rally fellow Carinthians and prepare for the future. He fled Trieste on the night of 28 April, travelling to Klagenfurt.

On the 29 April he spoke over the radio, “In these hours our first and foremost task is to keep our Gau free and pure.” He urged all to defend the borders of the land. To preserve Carinthia he declared on 4 May that Klagenfurt and Villach would not be defended against Anglo-American attacks, essentially declaring them “open cities.” Since he further believed it was possible a unified Carinthia would be supported by Britain and the United States, as it was in 1918 and 1919, he encouraged the preparation of arguments and arms. He entrusted execution of this hope to his recently founded Research Institute of Carinthia.

At the same time he severed his encumbrances to the South, having abandoned Istria, he now turned over the Ljubljana government to an anti-Communist Slovene National Committee. By reinforcing the notion of the Slovene’s right of self-determination, he hoped that Carinthians might use the same principle to their advantage.

On 5 May in a radio address Rainer stressed that Communism was the danger, not the Anglo- Americans. Also on 5 May he began talking with an all party group about a transfer of power to non-Nazis. The two sides quickly drew up a list of provisional government members and two days later Rainer reluctantly left office. In his view he resigned, he did not surrender.

The struggle for Carinthia was just moving to another phase, shortly before midnight on 7 May Rainer made a final radio speech. He urged his comrades to “keep the national honour safe” and exhorted them to “close your ranks in the struggle for a free and undivided Carinthia.”

The first proclamation of the provisional government reinforced these notions of Carinthian unity: “The new Provincial Government will consider as its primary task the maintenance of a free and indivisible Carinthia. German –speaking and Slovene-speaking Carinthians, gather around the Government. Long live democratic Carinthia in free Austria!”

After his resignation Rainer briefly visited his family and then went into hiding in a mountain hut, where he stayed for several days. Toward the end of the month he moved South into the Drau Valley where he met Globocnik for the last time. There they planned their next moves. Rainer decided to go to Spittal while Globocnik thought to take his chances in Italy, where he hoped to find friends to help him. In the early morning of 31 May, however, units of the British 8th Army, led by a local guide, climbed up to their mountain hut and swept down on the unsuspecting duo and their entourage.

Taken to a castle near Paternion they were briefly interrogated, Rainer admitted to his identity, but Globocnik maintained he was a businessman, until caught out by a subterfuge. At that point he abandoned hope, bit through a cyanide capsule, collapsed and died. The British assembled the Nazis held in the castle, including Rainer, and photographed them by the body of Globocnik.

Rainer’s death is a bit obscure he lived at least two, and probably four or five more years. After extensive interrogations by the English he was taken to Nuremberg where he was a witness for Arthur Seyss-Inquart, testifying on events leading to the Anschluss.

He wrote an extensive memorandum explaining his activities as Carinthian Gauleiter and governor. He was then moved to Dachau, where he remained for several months. Here he had a chance to escape but did not because he felt that would be admitting guilt. He also believed that the British had promised him he would be tried in an ordinary Carinthian court and not be surrendered to the Yugoslavs. In the end, however, he was turned over to the Yugoslavs in February 1947 and tried in a military court along with thirteen others.

He attempted a defence based on minimising his own responsibilities and even claiming ignorance of what was happening, at times he acted obsequious, trying to show how he had really helped the Slovenes. At other times he attempted to lay blame on his associates and subordinates. All arguments proved weak, Rainer and eleven co-defendants were found guilty and sentenced to death. When and how he finally died remains a mystery, although new evidence confirms him alive and collaborating with the Yugoslavs until at least 1949.

The careers of Rainer and Globocnik were not unlike others in the Third Reich, the story of their lives clearly places them into well defined, if different Nazi groups. Rainer fits into what Jonathan Petropoulos, in a recent book on Nazi politics, describes as the “quasi-autonomous chieftain of a particular territory,” one who viewed himself as a “prince.”

The theory and practice behind Rainer’s declaration that “I controlled the Adriatic Coastland,” confirms his role as the prototype Gauleiter or Reichsleiter. He like other chieftains, had his fiefdom from the Fuhrer, and he like the others gave his loyalty to Hitler.

But there is also another category for Rainer ,he was part of the self-assured Nazi elite, those who had developed self-images whereby each thought himself to have special and unique abilities. The author of this phrase was writing primarily of the Hitler’s, Himmler’s and Goering’s, but it also a description which applies to Rainer. He saw his abilities as the practical intellect, the able administrator and a man who would reach the highest levels of Party and State.

For Globocnik, of course, there are different categories, Ronald Smelser in his biography of Robert Ley provides one, “Ley was an important prototype of a certain Nazi – one whose fanaticism, idealism, and commitment to Hitler and the movement, made him an ideal “old-fighter” but whose inadequacies in the management of power, whose inability to gauge means to end, would cripple the effectiveness of the regime and eventually lead to its destruction.”

Globocnik like Ley easily fits this description, he had ambition, drive, and ruthlessness, but he never made the transition to power, he continued to be the free-wheeling, irresponsible opportunist, the sadist capable of bestiality but lacking personal confidence and ability which would have allowed him to function as an independent man, a commander of others.

Rainer and Globocnik were thus not so different from many others in their world, but what made them unusual in the Hitler entourage was their friendship. It continued despite significantly different levels of success, a number of factors help explain the lasting comradeship. There was the shared interest in the problem of “racial party” an interest which sprang, like Hitler’s from their birth on the fringes of cultural Germany. Throughout their lives, whether separate or together, whether dealing with Jew or Slav or Italian, they were concerned with the threat to things German.

This intense nationalism was then reinforced by their shared experiences during the illegal times in Austria, they worked closely together four years of prohibition, they collaborated in seeking power for Austrian National Socialism. Subsequently, they maintained their special connection even when they were separated. But what is particularly intriguing is that their friendship endured despite major character differences, Rainer was clearly the more capable, intelligent, principled and successful. He showed confidence, competence and character from beginning to end.

Globocnik after 1938, could not claim these attributes, he became instead a convenient tool of others in Vienna, Poland and Trieste. Where Rainer sought power, acquired it, and enjoyed using it. Globocnik sought power, found it, but did not know how to keep it. Always the faithful lieutenant, Globocnik hoped to obtain fame as conveyor of the Jewish extermination, then after 1943 as the faithful comrade to the head of the southern fiefdom.

In the end Globocnik achieved infamy, while Rainer, if not achieving fame, at least preserved the unity of Carinthia. He had the distinction of being the only Governor in the Third Reich to transfer power peacefully to his successor.

*Article (excluding footnotes) re-produced with full permission of the author for the H.E.A.R.T. Website, by Chris Webb

Copyright: 2010 M.W H.E.A.R.T

|

..jpg)

%20in%20Vienna.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)