Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos The Lodz Ghetto Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| ||

Radogoszcz Police Prison Lodz Ghetto

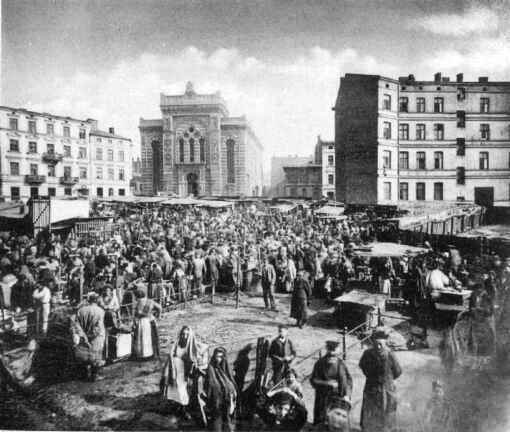

Before the Second World War Radogoszcz was one of the oldest villages and districts of Lodz. In the early 1930’s Samuel Abbe built the biggest, three storey factory building in the area near to the crossing of the Gen. J. Sowinskiego (modern name) and Zgierska streets. It was accompanied by a single-storey shop floor with a characteristic saw-blade roof and a building serving both administrative and living purposes.

In August 1939 the factory buildings were taken over by the Polish Army and after Lodz had fallen to the Nazis, the Germans took over the buildings as a German sub-unit, which were stationed there till mid-October 1939.

Subsequently the premises were turned into a relocation camp, several thousand people from Lodz and the immediate area were incarcerated there. At first the people were placed in the four –storey building and the adjoining shop-floor. By the end of 1939 most of them were taken to the General Gouvernment, as well as to the Krakow and Nowy Targ regions.

The remaining relocated detainees were moved to the shop –floor, while the main building now became a place of detention for prisoners from a transit camp in the Michal Glazer Radogoszcz factory in 55 Krakowska Street.

Thus, till the end of June 1940, both the transit and a relocation camps were located together. On the 1st July 1940 the transit camp was transformed into the Extended Police Prison, and the last deportees were removed from there by the end of 1940.

Radogoszcz prison took on a more sinister role from the first days of November 1939, it was then that the Nazi authorities began to arrest members of the Lodz intelligentsia – such as teachers, local and state bureaucrats, social and political activists, and artists.

Among the arrested were Polish citizens of German and Jewish origins. The arrests were a purposeful action aimed at depriving Polish society of its leaders. The arrests were made on the basis of proscriptive lists, and after a trial by a summary court, people were usually sentenced to death. They were executed immediately afterwards in the forests surrounding Lodz and the bodies were buried at the site of the murders.

From the 10 November 1939 until early January 1940 about 2,000 people, both men and women, were at some time interned in the camp, of which about 500 were “tried” by a summary court and shot to death.

The factory buildings were not adapted in any way to house people prior to the establishment of the camp, there was no kitchen in the buildings, just a pot from brewing coffee. There were no beds in the rooms. The living conditions were extremely oppressive. The whole camp was surrounded by a barbed wire topped wall in which the corners held watchtowers for the guards.

The prisoners did not succumb to starvation and disease thanks to the Polish Committee for Aiding Those Detained in the Radogoszcz Camp, established with the permission of the Gestapo. The members of Lodz factory –owner’s families, the Bidermans and the Keiserbrechts, among others, played a prominent role in the committee.

At the end of December 1939, the prisoners were moved to the Abbe’s factory building, where necessary works had been done, financed by the Committee for Aiding. A kitchen and baths were prepared, and rooms were furnished with wooden bunk beds.

The last group of prisoners was placed here on the 5 January 1940 at 10.00 a.m. The Polish women remaining in the Glazer plant were set free the next day. A group of Jews might have been detained in the plant till mid-1940.

The Extended Police Prison (Erwetertes Polizeigefangnis) in the factory buildings of Samuel Abbe was the biggest prison in Lodz and the surrounding region during the Nazi occupation. It was for men only, and the prisoners were sent to other prisons, typically in Sieradz, Leczyca and Wielun, as well as to forced labour camps, first in Ostrow Wielkopolski, then in Sikawa in Lodz, and concentration camps – mostly Dachau, Mauthausen- Gusen and Gross Rosen.

It is not widely known that between May and November 1940 a sub-camp of Radogoszcz prison functioned on a farm of the Kons, co-owners of Widzew Manufacture. Men detained here were used as labour for different work done in Lodz. They were housed in a building that does not exist today, situated at the junction of Al. J. Pilsudsiego and Konstytucyjna streets.

The conditions in Radogoszcz were bestial, so much so that those leaving the prison for concentration camps were grateful that they did not have to stay in “this hell.”

Wladyslaw Zacharowicz incarcerated in Radogoszcz prison from the end of 1942 to the beginning of 1943, recalled after the war:

“When we arrived in Gusen concentration camp after leaving Radogoszcz we breathed a sigh of relief.” Prisoners were dying in the Radogoszcz prison every day as a result of starvation, disease, exhaustion, and sadistic practices. The Radogoszcz guards were particularly ruthless, creating inhumane conditions for the prisoners. There were approximately 60 -70 prison guards, armed with guns, whips and wooden clubs. Many of them were Volksdeutsche from Lodz.

Jozef Jankowski imprisoned in the prison from November 1941 until January 1942 recalled the commandant Walter Pelzhausen: “Pelzhausen was a degenerate, he would brutally beat anybody crossing his path, he would kick you all over your body, even after you collapsed. The beatings were so severe that after a few days people were dying, especially that we also suffered malnutrition.”

Apart from the commandant, the most brutal prison guards were Jozef Heinrich, nicknamed “bloody Joseph,” and Brunon Matthaus, alias Matuszewski, nicknamed “Doctor,” or “Mateus.”

Virtually each prisoner would get the “welcome beating” on entering the prison. Kazimierz Michalski, a prisoner incarcerated in Radogoszcz prison from the 7 November 1940 to April 1941, recalls the tortures, where the prison guards stood on each flight of stairs, beating the prisoners:

“On 11 November 1940 we had a “parade” lasting from 6am till 6pm. We were forced to, in turn, crawl on the ground and run up and down the stairs.” On average there were between 500 and 1,000 people interned in the prison, they were located in three rooms of the main building, covering the whole floor, 500 sq metres each. The factory windows in the rooms were first painted over and later, in mid-1942 bricked up to three-fourths of their height.

The third floor was allotted to people held by the Gestapo; on the second floor there were prisoners of the Kriminalpolizei. The first floor housed the prisoners holding a work post and those of German descent. Also Russian Prisoners of War were detained here, yet they were carefully separated from the rest of the inmates.

The base floor served at first as an isolation ward, acting as the sick ward. After, when a bigger sick ward was opened in the single-storey building, several workshops operated here, producing wood works and shoes, both straw and regular. The prisoners of Radogoszcz wore their own clothes. In 1940, for example, the prisoners wore colourful squares – a red square for political prisoners, a green square for thieves, and a yellow square for black –marketers and smugglers.

At the end of 1942 and in the beginning of 1943 prisoners condemned to death had a yellow “B” letter painted on the side of their trousers, on their backs and chests. The Jews imprisoned in Radogoszcz wore the Star of David on their chests and backs, but Jews were imprisoned in this prison until the 30 April 1940.

One of them was Teodor Wilenski, who lived in Lodz and was an amateur painter, he was imprisoned in Radogoszcz in 1942 and he made portraits of his fellow prisoners in return for food, and some of his pictures have survived.

Prisoners recall that Wilenski attracted the attention of the commandant Pelzhausen, one of them Boleslaw Kowalczyk, recalled the following:

“At the end of 1942 one of the Germans gave him a piece of meat, which was noticed by Pelzhausen. He started a three-day round of tortures, trying to make Wilenski confess who had given him the meat. The man was in a terrible state, all bruised and covered in blood.

The prison doctor Winter sent him to Radogoszcz hospital during Pelzhausen’s absence. However, when Pelzhausen noticed Wilenski was missing he had him brought back and kept beating him. The next day the doctor sent him to the ghetto hospital. Later I was told Wilenski died there of his wounds.”

The sick ward, contrary to what the name would suggest, was not used for treating sick prisoner’s, it was more like an additional torture room. Leszek Kieszkiewicz recalled during Pelzhausen’s trial:

“Pelzhausen once visited the isolation ward. He noticed several people staying here for a longer time. He asked the German paramedic Mateus; “Why are they still alive? Following that, Mateus prepared a cold bath for the prisoners, who died within one week. These were Stanislaw Wozniak, Zygmunt Bartczyk and Leon Nowak. One had kidney problems, one lung problems, and the third had heart disease.

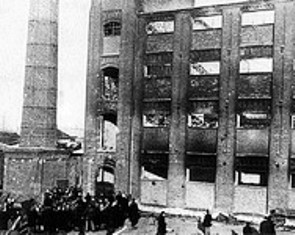

The long list of crimes committed in Radogoszcz prison was concluded by the most hideous one – the Nazis set fire to the prison with the prisoners still inside on the night of 17 January 1945.

Around midnight on the 17/18 January 1945 the prison staff began the extermination of the remaining prisoners. The first to be murdered were the sick prisoners lying in the sick ward situated in the single-storey building, then the functionary prisoners on the base floor of the main building. Next the executioners started killing people interned in subsequent rooms.

After the prisoners had resisted the guards in one of the rooms, they withdrew and set the building along with those still alive in it, on fire. The fire and executions killed about 1,500 people. Only about 30 prisoners survived, some of whom were hiding in a water tank standing on the highest landing of stairs in the building.

Water from this tank had been used in the boiler room, the kitchen, the bath and other prison rooms. Among the survivors were: Stanislaw Jablonski, Boleslaw Poplawski, Adam Sowiak, Antoni Szmaja, Jozef Zielinski, Zdzislaw Skowronski and Franciszek Zarebski

Feliks Blotnicki recounted those terrible events:

“About 4 in the morning (on Thursday) a few Gestapo soldiers came and took a roll-call. They ordered us outside those who did so were shot on the first floor. Then, as we noticed the prison was on fire, some of us, me included, climbed a ladder and a bench to the roof, and when the fire made a hole in the roof, we jumped into the kitchen. There were only nine of us in the kitchen, the others having been shot while jumping.”

Franciszek Brzozowski also remembered that day:

“Some time later we noticed the prison was on fire. My colleagues began jumping out of the windows, to the courtyard, but then the Nazis shot them dead. I escaped to the roof through a squint window. There was a water tap on the roof, so for some time we poured water around and sat there, a dozen people.”

Kazimierz Michalak, who used to be sports journalist in the Echo daily before the war, a resident of nearby Zgierz, and himself had been imprisoned in Radogoszcz prison during late 1944 and early 1945, but was transferred to the prison on 16 Sterlinga Street, just before the fire and the massacre.

On the night of the 17 January 1945 he escaped during the prison evacuation, when the prisoners were marched along the road to Pabiance. Despite suffering from exhaustion, when he was informed of the massacre at Radogoszc prison, he visited the site and took photographs of the charred remains of both the inmates and the prison building itself.

On the 28 January 1945 a mass was held next to the walls of the burned prison, to commemorate those murdered at Radogoszcz prison, 2,000 people participated in the ceremony. The prison staff managed to escape from the advancing Russian forces, the vast majority have remained un-punished for their appalling crimes, however the American forces captured former commandant Walter Pelzhausen and he was taken back to Lodz to stand trial.

He was tried between the 8 and 12 September 1947 in the District Street in Dabrowskiego Square, where he was found guilty and condemned to death and executed on the 1 March 1948.

Today the former site of Radogoszcz prison is both a memorial and a museum, and it should be recognised as one the most impressive, particularly the museum, which covers not only the prison, but all important aspects of the German occupation of Lodz from 1939 -1945, with many exhibits and photographs.

Sources:

The Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto 1941-1944 edited by Lucjan Dobroszycki published by Yale University Press New Haven and London. 1984 A Book of Lodz Martyrdom, published by the Museum of the Independence Traditions in Lodz 2005 Holocaust Historical Society Polish State Archives Private collections

Copyright Chris Webb & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2009

|