Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Occupation German Occupation of Europe Timeline

-

[The Occupied Nations]

Poland Austria Belgium Bulgaria Denmark France Germany Greece Hungary Italy Luxembourg The Netherlands Norway Romania Slovakia Soviet Union Sudetenland | ||||||

The Destruction of the Norwegian Jews

Between the end of the 13th century and 1814 Norway was ruled by Denmark. In 1814 the European great powers decided that Norway should enter a personal union with Sweden under the Swedish King, thereby delaying its independence until 1905. But in 1814 a wave of patriotism swept the country.

n 1814, Norway acquired its first constitution. This document was relatively liberal, but it stated that the official state religion was Lutheran Protestantism and that Jews and Jesuits were forbidden from entering the kingdom.

Of the numerous constitutional drafts drawn up before the constituent assembly, only a couple prohibited Jews from entering the country, however it was the version put forth by cleric Nicolai Wergeland that was the most virulently anti-Semitic, in his draft he wrote the following clause: "No person of the Jewish creed may enter Norway, far less settle down there".

The debate on the so-called "Jewish clause" was long and heated, however ban on Jews entering Norway was passed and was not to be lifted until 1851 after which time the Jewish population grew slowly until the early 20th century, when pogroms in Russia and the Baltic states increased the number of immigrants.

An further increase in Jewish immigration came in the 1930s, as Jews fled Nazi persecution in Germany and areas under German control. By 1941-1942 the Jewish population of Norway numbered roughly 1,000 households and approximately 2,200 individuals.

The Jewish minority was primarily involved in the business sector. Norwegian Jews owned about 400 enterprises. About 40 were professionals , the remainder craftsmen and artists. Few Jews were employed in the public sector or as farmers or fishermen.

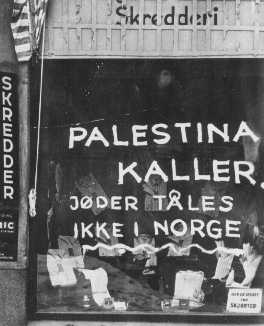

There were two main communities, in Oslo and Trondheim. In both cities the Jewish population enjoyed a lively cultural life, and the Jewish communities operated numerous religious institutions and cultural organizations that ran various educational and welfare programs. Though the Jewish minority was small and widely dispersed, several anti-Semitic stereotypes took hold in popular literature in the early 20th century. In such books by the widely read authors Rudolf Muus and Øvre Richter Frich, Jews are described as obsessed with money and sadistic. In 1920, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published in Norway under the title "The New World Emperor".

The country's immigration policy shifted following World War I to a far more restrictive line, and Jews were particularly singled out. The ministries of justice and foreign affairs were often at odds on the issue of Jewish immigration, but in practice the policy made it difficult for Jews to immigrate or settle in Norway.

Restrictions were justified on an economic basis, Jews would either create destructive competition for Norwegian merchants and tradesmen, or freeload on public assistance. Some were based on purely political concerns, Jews as communists and other subversive elements would create political instability, or general xenophobia against "foreign" groups. Whether the immigration policy was driven by the characterizations above, or vice versa is not clear.

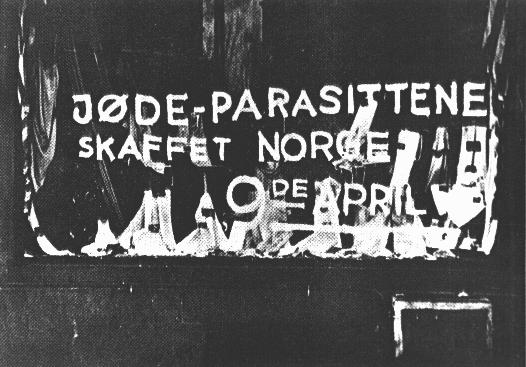

Anti-Semitism climaxed when the Germans invaded Norway and Denmark on 9 April 1940, in a combined attack, and despite the gallant efforts of the Norwegian, British, Polish and French forces the Germans proved too strong. Norwegian armed resistance began with the first great act of sabotage (though it lacked any military significance), with the bombing of the Lysaker Bridge linking Oslo to its airport in Fornebu.

On 1 February 1942, he took power in Norway as the Minister President, and set about encouraging Nazi values and promoting the German cause in Norway. German authorities under the leadership of Reichskommissar Josef Terboven, put Norwegian civilian authorities under his control. This included various branches of Norwegian police, including the district sheriffs, criminal police, and order police.

The Jewish community of Norway was hit hard by the policies of the Nazis authorities and first anti-Jewish measure was introduced just a month after the beginning of the occupation, in May 1940, when radios of Jews were confiscated. In October 1941 registration of Jewish property started; a number of Jewish owned firms and businesses were confiscated. The programme of anti-Jewish measures continued with the stamping of Jewish identity cards which began in January 1942, Jews were to have a red “J” stamped in their identification papers. During this period there were some arrests of Jewish men , who were sent to prisons and labor camps inside Norway.but this did not lead to the mass arrests of the 1,700 Jews, of which the majority were refugees from the Reich, concentrated in Oslo.

Quisling appointed a 'Liquidation Board of Confiscated Jewish Assets.' Jewish households and businesses were treated as bankrupt, thus enabling their assets to be sold. The Jewish estates were liquidated, but continued to exist as legal entities, thus permitting expenses to be levied against them. This practice remained in effect even after the war, when a democratic government was established again in Norway. "The belongings of the estates were distributed according to the interests of the Quisling regime. All gold and silver objects and wristwatches were given to the German security police. The assets of Jews originally from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia were given to the German authorities. By the end of the war, the 'Liquidation Board' had used approximately 30 percent of the value of the Jewish properties for its own administration. A reception camp for Jews was soon established at Berg, near Tonsberg, and during June 1942 a general registration for Jews took place, and the confiscation of all Jewish property was completed by October 1942.

On the 2 September 1942 the Chief Rabbi of Norway, Julius Samuel, was ordered to report to the Gestapo. his wife Henriette Samuel urged him to go into hiding, or to flee, but he told her: “As Rabbi, I cannot abandon my community in this perilous hour.” He was then arrested, together with 208 Norwegian men, they were sent to an internment camp at Berg, south of Oslo.

Then on the 25 October the police, ably assisted by the Hirden, the National Socialist militia founded by Vidkun Quisling, seized some 209 Jewish men and boys over sixteen years of age.

They were sent by sea from Norway to Stettin on the Nord-Deutscher Lloyd steamer Donau and then continued their journey by rail to the death camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland. Then on the 26 November the Norwegian police assisted by the Hirden, the National Socialist Militia founded by Vidkun Quisling, carried out another round up of Jews in Oslo.

At 04.30 hours one hundred taxis and 300 men of the Hirden and Norwegian police divided into approximately fifty groups were charged with collecting ten Jews each. A Norwegian Police officer called Knut Roed planned the action.

The trip with steamer Donau started in Oslo from the so-called American Quay at 2pm in the afternoon with 532 Jews on board. The steamer docked in Stettin on the 30 November 1942 and this transport arrived in Auschwitz- Birkenau on the 1 December 1942

Among the Jews deported in this transport is Professor Dr. Bertold Epstein, professor of paediatrics at the University of Prague, who emigrated to Norway after the Germans occupied Prague. He receives the camp registration number 79104 and becomes a prisoner physician in the men’s camp at Birkenau, in the Buna auxiliary camp and in the Gypsy camp, his wife dies in the gas chambers.

This transport consisted of 532 Jewish men, women and children, of which 186 men are admitted into the camp, the remaining 346 people are killed in the gas chambers at Birkenau.

Some of the Jews rounded up in November 1942 were not included in the above transport to Poland but were imprisoned at Bredveit prison in Oslo to await deportation to Poland.

On the 24 February 1943, the Bredveit prisoners, along with twenty-five people from the concentration camp at Grini (built in 1939 as a prison for women – but turned into a KZ by the Germans) boarded the Gotenland steamer in Oslo. The ship departed the following day carrying 158 deportees, landing at Stettin on the 27 February 1943.

The deportees then travelled to Berlin, where they stayed overnight at the Levetzowstrasse Synagogue. They then travelled by train and arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on the 3 March 1943.

The majority of these transports are murdered in the gas chambers, it is thought that out of these transports only thirteen survived the war, some were employed at the Monowitz sub-camp.

Of the remaining 930 Jews they succeeded in escaping over the border into neutral Sweden, with the help of the Norwegian people, who risked their own lives, to help them reach safety. Among those saved was Henriette Samuel, the wife of the already deported Chief Rabbi.

Not only was she saved but also her children, a twenty-five year old Norwegian girl, Inge Sletten, a member of the Norwegian resistance, not only warned her of the impending deportations, but took her and the children to the home of a Christian friend and a week later arranged for them to be smuggled across the border into neutral Sweden, together with forty other Jews.

Others remained in hiding, or were exempt from deportation through marriage to Aryans and interned in camps. The behaviour of the Swedish Government deserves special recognition.

After the first sailing of the Donau Dr Richert, the Swedish Minister in Berlin, proposed that his country should receive all the remaining Jews in Norway. True to his usual stance, Weizacker, the Chief State Secretary of the German Foreign Office, refused even to discuss the matter, and informed Ribbentrop, that he had told Dr Richert that “the project would not stand a chance.”

There was, nevertheless a liberal dispensation of naturalisation papers by the Swedish Consulate of which Terboven, the Reichskommissar complained in March 1943.

Altogether approximately 767 Jewish men, women and children were deported to Poland, mostly to Auschwitz, and 26 survived the war. The former house of Norwegian collaborator and dictator, Vikun Quisling, has become the Norwegian Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, opened on August 23, 2006 as a research center.

It is located on the Oslo Fjord, with views of the harbor where Norwegian Jews were shipped to Stettin and Auschwitz.

Sources:

The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger – Vallentine Mitchell &Co Ltd 1953. Atlas of the Holocaust by Martin Gilbert, published by Michael Joseph Ltd 1982 Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Israel Gutman, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990 Auschwitz Chronicle by Danuta Czech, published by Henry Holt New York 1990 Bjorn Westlie, Coming to Terms with the Past: The Process of Restitution of Jewish Property in Norway, Institute of the World Jewish Congress. Holocaust Historical Society. * Special thanks to Olaf Nielsen

Copyright Victor Smart H.E.A.R.T 2008 |

'

'