Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Other Camps

Key Nazi personalities in the Camp System The Labor & Extermination Camps

Auschwitz/Birkenau Jasenovac Klooga Majdanek Plaszow The Labor Camps

Trawniki

Concentration Camps

Transit Camps | |||||||||||||||

Stutthof Concentration Camp

Sztutowo is the name of a fisherman’s village, located 34 kilometers northeast of Gdansk / Danzig and 3 kilometers from the Baltic coast. With the German invasion of Poland, Sztutowo became Stutthof and entered the halls of history as the wartime site of an infamous concentration camp.

Before the war a wooden home for the elderly was situated in a forest near the village of Stutthof at the base of the Vistula Sandbank, belonging to the Free City of Danzig, now Gdansk.

The site was ideal, beautiful fir and pine forests spotted here and there with silver-birch and oak, together with extensive plains which gave the impression of a land of quiet and beauty. It was therefore not surprising that a home for the elderly was established in one of the most charming corners, a beautiful large house, not far away a glade and at arms length more forests.

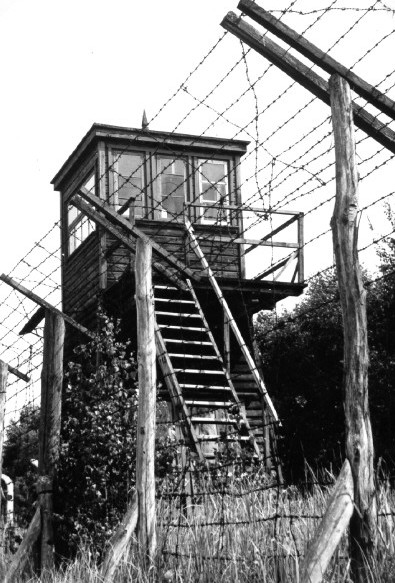

In the middle of August 1939 a group of a dozen or so prisoners were brought to this area by SS-men from the Schiesstange prison in Danzig and they fenced in a small clearing and erected temporary wooden constructions.

The SS-men supervising the initial constructions belonged to the SS- Wachsturmbann Eimann, after their commander Kurt Eimann, a five-hundred strong detachment established to “solve the Polish question” in the Danzig area.

One group from this detachment under the command of SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Max Pauly were responsible for organising the camp at Stutthof. The site chosen was conveniently situated with good connections to Danzig and Nowy Dwor and also in the triangle of the Baltic Sea, and the Vistula and Nogat Rivers, which for all practical purposes prevented prisoners from escaping.

Other notable members of the SS staff at Stutthof were:

Returning to the location of the camp, the surrounding ground was wet, under the thin layer of sand were marshes and peat-bogs, the water of which lacked lime, which proved deadly to some prisoners.

Based on a list previously drawn up by the police and Selbstschutz, about 1,500 people, classed as “undesirable Polish element” – were arrested in Danzig on the night of 31 August – 1 September 1939. They were mostly socially and politically active Poles from the Free City of Danzig.

Those arrested were taken to such assembly points as the Emigration Barracks in Nowy Port, the Victoria Schule in the former Holzgasse in Danzig. The following day, after selecting the tradesmen and specialists from among the prisoners, the first transport of about 250 civil prisoners were transported to the area designated for the Stutthof camp on 2 September 1939.

Such was the beginning of Stutthof’s official existence, in view of the growing reach of Nazi policies the camp was rapidly expanded by using the prisoners as forced labourers.

According to the camps accounts, which were scrupulously maintained, by the end of March 1940, 299, 459 Reichsmarks had been invested in Stutthof, the camp had also been expanded to accommodate several thousands prisoners.

Wlodzimierz Wnuk recalled;

“To the sounds of striking axes and crashing trees, a huge encampment is taking shape in the forest near the coast. Columns of emaciated men sag under the weight of bricks and iron bars, huge pine trunks cut into their shoulders, crushing them down to the ground.

Encircled by barbed wire, a long row of barracks has grown out of the ground cleared by the sweat and toil of the prisoners. The barrels of machine-guns glitter where the frozen guards stand by, in the ice-bound world around even their breath forms icicles.

Hovering above the camp are pulsating columns of smoke – as yet, still that normal smoke from burning wood.”

Stutthof was the first Nazi concentration camp to be established on Polish soil, and the last to be dissolved, it grew from 4 to 120 hectares, from 250 prisoners to a maximum of 52,000 prisoners at one time, the SS staff and guards numbered 1,056 on 1 January 1945.

The organisation of Stutthof was generally similar to other camps:

Stutthof was not immediately granted the status of a state concentration camp, for three years it came under the Danzig / Gdansk police and initially was a camp for “civil prisoners,” later a labour camp, being called the Sonderlager Stutthof.

Despite all the efforts of the SS and Police in Gdansk Richard Hildebrandt, Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfuhrer –SS refused to give Stutthof official concentration camp status. It was only after Himmler’s visit on 23 November 1941 that this reluctance was overcome, and Stutthof became an official concentration camp from January 1942.

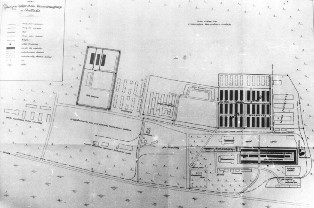

From January 1942 the camp which initially held a bare three to four thousand prisoners, expanded rapidly. Prior to the expansion, the camp – later called the “Old Camp” – had consisted of eight barracks for prisoners, a workshop, stores, baths and hospital.

The camp offices occupied two barracks, there was also a brick-built headquarters, kennels, the “Rabbit barrack,” a hothouse and to the west of the camp, the commandant’s villa and accommodation for the SS staff.

The plans for the “New Camp” foresaw the completion by 1944, of thirty larger barracks, twenty for prisoners and ten for armament workshops DAW (Deutsche Ausrustungswerk).

A special camp (Sonderlager) was built one and a half kilometres from the New Camp at the beginning of 1944. The prisoners incarcerated there were called “Haudegens.”

Many new, brick-built blocks were erected between the New Camp and the Sonderlager, many planned installations, such as kitchens, washrooms etc were planned but not completed.

Towards the end of 1944 huge transports of Jews were brought to Stutthof they were destined for extermination, also transports of Gypsies were sent to the camp, for the same end result.

The arrival of masses of Hungarian, Greek and Czech Jews compelled the camp authorities to build a further ten barracks to the north of the New Camp. East of the New Camp large factory sheds were erected, setting up branches of the Focke-Wulff plane parts – submarine parts were manufactured in the so-called Delta -Halle. Still further to the east was the so-called Germanenlager, which accommodated, among others, Norwegian policemen who had refused to co-operate with the Quisling government, and Finnish sailors.

The number of nationalities of the prisoners increased and the social structure of the camp changed with the influx of new transports. The first group of about 450 Jews from the Free City of Danzig arrived on 17 September 1939.

After the capture of Gydnia almost 6,000 Poles were temporarily rehoused in Stutthof in mid-October 1939 and from the autumn there were systematic influxes of prisoners from the Gestapo prisons in Gdansk, Torun, Bydgoszcz, Plock, Grudziadz, Elblag.

In addition small groups such as scouts from Gdynia, Polish social workers and those politically active, such as members of the underground resistance movements such as Gryf Pomorski and the Home Army, as well as pupils from the Polish grammar school in Kwidzyn.

They played an important role in the life of the camp struggling with the group of professional German criminals who had been brought in during 1941 to take on the role of functionary prisoners.

Russian prisoners began to arrive after the German invasion of Russia during 1941 and some former members of Lithuanian and Latvian governments were imprisoned in Block 11, as so-called honorary prisoners.

Shortly, afterwards these were joined by a dozen or so Lithuanian intellectuals, including Professor Balis Sruoga, and Dr Antanas Starkus. At the end of 1943 a group of one hundred and fifty Danish communists including Kaj Moltke, and Paul Nielsen were imprisoned in Stutthof. German communists were also incarcerated in Stutthof.

A unique page in the history of Stutthof was written in 1944, after the Red Army victory in Stalingrad and the relentless offensives the Germans were forced to evacuate their Eastern empire, and the camps in those regions.

Mass transports then began to arrive at Stutthof from Riga, Kaunas, Konigsberg, Bialystok and Lublin. The greatest number of transports to arrive in Stutthof came from Auschwitz, and also worthy of mention of the transports from the Pawiak prison in Warsaw, and following the Home Army uprising in 1944, from the evacuation camp at Pruszkow.

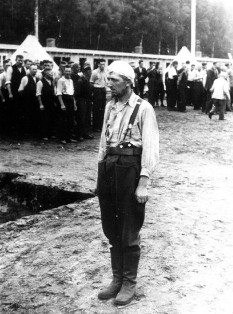

It was an accepted custom that when each group of new arrivals entered the camp through the main gate, the so-called “Death Gate,” the first formality completed by the political department was a brutal welcoming by the SS officer.

Zbigniew Raczkiewicz recalled what the SS officer said to new arrivals:

"From now on you are no longer a person, just a number. All your rights have been left outside the gate- you are left with only one and that you are free to do – leave through that chimney.”

Newly arrived prisoners were grouped in the “Old Camp” square - here they sometimes waited a whole day or even longer, irrespective of the weather or time of year. Prisoners were beaten before they were entered on the camp register. They were forced to strip on the camp square, and they had to hand over all personal possessions to the camp stores.

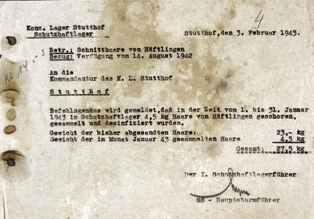

This was followed by the shaving of both men and women, then the body-search for hidden valuables, and then finally a bath, the prisoners were then issued with camp clothing and a number, and their personal details recorded.

This was followed by a period of quarantine in Blocks 17, 18, 19 of the “New Camp” which lasted 2 to 4 weeks. The prisoners did not work whilst in quarantine, in the morning they performed drill under the supervision of the block or barracks chief, whilst in the afternoon there were various records to be completed, particularly for the Arbeitseinsatz for the allocation of forced labour.

After quarantine the prisoner was assigned to a barrack where he or she was to sleep and also assigned to a particular work commando. The male prisoners lived in fifteen barracks in the “New Camp.” Each barrack was divided into two equal parts A and B. Each part had a vestibule, washroom, lavatory, day-room and sleeping quarters.

The latter was furnished with three-storey bunks which had paper mattresses filled with wood shavings, similar pillows and cotton blankets.

The living conditions in the barracks depended to a large extent on the barracks chief, and over-crowding that featured with there often being 3 or 4 times more prisoners living in these barracks than originally planned for.

Some prisoners did not enter the camp proper, they arrived with a death sentence for any number of offences against the Nazis, Krzysztof Dunin- Wasowicz recalled:

“In the afternoon, when Ludtke wearing his ironic smile arrived at the Rapportabteilung with a card in his hand, we all knew what was to come. The condemned who had been brought to the Rapportabteilung waited about half an hour, then just before the roll-call Chemnitz and Foth arrived and took them towards the crematorium. There they were either shot in the back of the head, or hanged.”

Sometimes transports arrived from Gdansk people were taken immediately and locked in underground window-less cells in a small building at the side of the “Old Camp.” These prisoners were usually executed by shooting before the evening roll-call.

Another killer was typhus; there were several epidemics in 1942, spring of 1943, then the most serious the end of summer and autumn of 1944. Even if the medical staff of the camp wanted to help the prisoners to regain their health, they were, to all intents and purposes helpless in the face of this disease and others.

Those who fell sick did not die just from the illness, the incurables or chronically, such as those with tuberculosis were murdered by means of injections of phenol or drowning in the bath, at night. The camp doctor had the right of selection to the gas chamber.

Tragic games were also organised, during which the SS butchers, dressed up as doctors, received the sick, keeping up appearances and formalities, then when measuring their height, the prisoners were shot in the back of the head from a specially constructed appliance. The corpses were taken outside, the blood wiped up and the next victim was politely requested to enter.

When the new hospital was opened the living conditions of the sick greatly improved, but on the other hand the mortality rates increased rapidly in 1943. The new hospital accommodated on average 600 to 1,000 sick, additionally the outpatients section treated 500 persons per day.

In 1944, a Jewish hospital (Judenkrankenbau) was isolated in barrack 30 for the mass transports of Jews, conditions were dreadful, Jewish doctors received neither medicines nor dressings.

The Camp authorities believed they were all destined for extermination therefore treatment was unnecessary. Barrack 30 became the “finishing off” barrack, where food was frequently not distributed, and prisoners died of famine fever.

Work was another method of extermination, the prisoners worked in groups called “kommando’s, “ each under the command of a Kapo, the prisoners were not only employed to cover the camp requirements, but also those of German firms, located inside and outside the camp. Sub-camps were established to supply cheap labour for various firms located some distance from the main camp.

As a rule the working day commenced about six or seven o’clock in the morning and finished between five and seven o’clock in the evening. The working day usually lasted around twelve hours, with an hours break for a meal. On Sunday, the prisoners worked till mid-day, when after that they were spared from work.

The lightest work included assisting in the camp administration, stores, repairing of clothes, in the kitchen. It was also considered to be of advantage to obtain employment in the camp carpentry, joinery, painting, shoemakers, saddlers, lock-smith and gun-smith workshops.

At least working inside the prisoners were spared from the worst of the brutal weather, but not of course from the brutal kapo’s. The workshops constituted branches of the DAW working for the needs of the German army.

Prisoners were also employed in the firms of Dehlert and Rommel which carried out building and road work in the Stutthof camp. There was also a branch of the Focke-Wulff works and naval armaments parts were produced in the so-called Delta-Halle

One of Stutthof’s most brutal working kommando’s was the “Waldkolonne,” which was employed in clearing the terrain for the camps installations. The name was later changed to SS und Polizei-Bauleitung,” which was divided into the following working groups:

To be allocated such work was as good as a death sentence, receiving only 1,000 calories per day, the only chance of survival lay in escaping. Hunger played a leading part in the extermination of prisoners, for dinner the prisoners hurriedly swallowed a bowl of soup made from turnip, carrot or cabbage scraps. For breakfast and supper the prisoners received a piece of bread with a tiny portion of margarine or jam, supplemented with a mug of ersatz black coffee.

Similar exhausting work was also applied in many of Stutthof’s sub-camps. The most severe was at Police near Szczecin, a synthetic petrol plant, where Kozlowski – first a room supervisor and later even Camp Elder – gained dishonourable fame.

The work was also very hard at Schichau in Elblag, the Danziger Werft shipyard at Przerobka in Gdansk, in the brick-works of Hoppehill, in Graniczna Wies (a quarry).

The Jewish sub-camps consisted of working on five airfields in East Prussia, in wagon factories, on the building of fortifications for the Todt organisation in Elblag and Torun, and thousands of Jews lost their lives, serving the Nazis. Altogether over 25,000 prisoners worked in approximately forty-plus sub-camps.

Returning to the main camp of Stutthof, those prisoners who managed to endure the starvation, excessive work, beatings, disease might still be killed either by a shot in the back of the head , or be gassed in the gas chamber.

On Good Friday 22 March 1940 67 members of the Gdansk intelligentsia were shot outside the camp. Those, who lost their lives in this mass shooting were post-office workers, businessmen, priests, printers, journalists, lawyers, among them was Anastazy Wika Czarnowski – the former director of the Polish Post-Office, Mr Pawel Rozankowski, an engineer from the Port of Gdansk Council, Franciszek Krecki – a Polish economic and social worker, Bronislaw Komorowski – rector of the Polish church of St. Stanislaus in Wrzeszcz, Wladyslaw Pniewski – Polish teacher at the Polish Grammar School, Antoni Lendzion – member of the opposition in the Free City of Danzig “Volkstag.”

Many prisoners were executed by hanging, in public, to serve as a warning to others on a scaffold, initially erected near the crematorium, later in the parade-ground in the “New Camp.”

Executions usually took place just before dinner, on a scaffold set up between barracks twelve and thirteen. The scaffold consisted of two vertical beams, connected by a cross-beam on which two rings were hung, through which nooses were pulled.

The condemned men had to climb up a small ladder onto a plank set one metre above the ground. This plank was snatched from under the victims by means of a rope. In the late autumn of 1944 two Poles aged 17 and 19 were hanged in public at 12 o’clock mid-day.

Particularly memorable were the hanging of a young Pole for alleged sabotage, at the side of the Christmas tree which had been provided by the SS as an exceptional gesture, on 28 December 1944, and the execution of two Russian boys, who were brothers. Both were very young, the younger one crying, the older brother consoling him and uttering loud threats of revenge against the Germans by the Red Army.

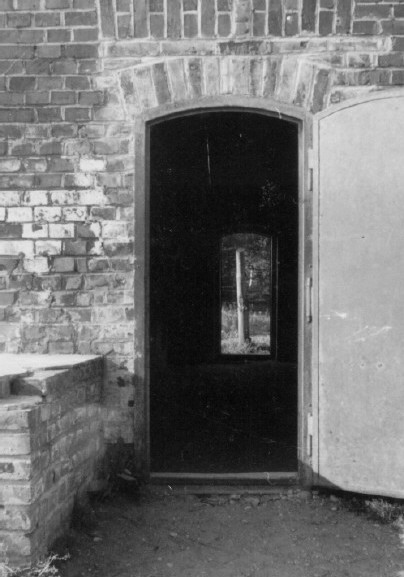

A gas chamber was built in the autumn of 1943, at first it was used to disinfect clothes but in June 1944 they started to murder prisoners in it using zyklon-B. In Stutthof’s small gas chamber Jewish transports of Hungarian, Greek and Czech Jews mostly transferred from the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp complex.

Maria Suszynska witnessed the arrival of such a transport:

“They arrived in a horrifying physical state, usually from other camps mainly Auschwitz to die here. They plodded on and on fatigued, with black faces, hair growing from their skin in bristle.

They plodded on and on staring with their huge black eyes with what seemed to be an inhuman expression. They wore neither sweaters or jackets only torn summer dresses, through the tears in which their grey bodies could be seen. They were without vests, gaunt with their pointed shoulders, sunken chests – they were more like some weird ugly birds.

In their hands they gripped pieces of bread, but were unable to eat. Were they aware where they were once more being taken?”

The SS –men had to think up new tricks to deceive the Jews, they were also gassed in a special railway wagon, the SS men wore railway uniforms, carried flags and whistles.

A total of about 50,000 Jews from various European countries passed through Stutthof during 1944, some of them were immediately directed to the gas chamber. Some of the stronger prisoners were crammed into the sub-camps, and then sent to Germany as the Russians approached.

During the initial stages of the camps existence the bodies of prisoners who had died or had been murdered were transported to Gdansk and buried in common graves at the Zaspa Cemetery.

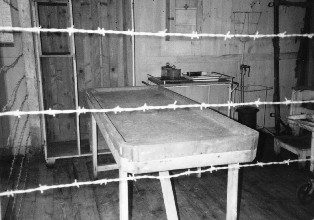

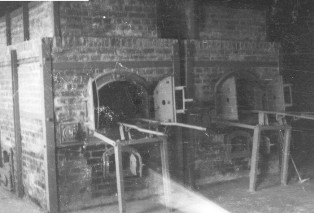

In September 1942 the Berlin firm Kori erected two brick stoves and raised an 18 metre high chimney, over the stoves a wooden roof was built, which quickly burnt down, and after that a brick structure was built.

A Red Army commission described the crematorium:

“The furnace is built of firebrick, with an opening at the front – through which the bodies were placed, also at the front, was an opening through which to remove the ashes, there are two hearths on the left of the furnace.

At the front there was also a small opening – 20cm in diameter – closed by means of a small door, with which to regulate the draught. All the openings were closed by means of iron doors 7-9 mm thick.”

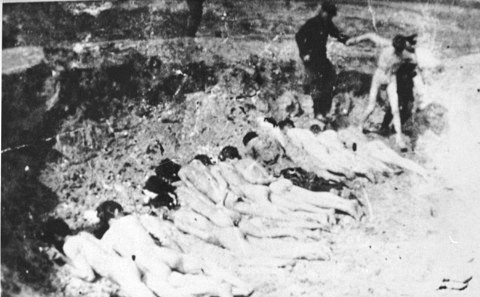

During the typhus epidemic in 1944 the crematorium could not keep up with disposing of the corpses, a crematory pyre was set up north of the “New Camp.” The pyre was constructed so that there were alternate layers of corpses and logs or boards, then splashed with mazut to make sure it burned better.

There were very few successful escapes, in fact they were exceptional, but some prisoners managed it. These included Marcjan Czarnecki, Karol Viola, Wlodzimierz Steyer, Stanislaw Jankowski and two Englishmen whose names were not known.

On 12 January 1945 the Russian army started their Winter Offensive, the German camp authorities had already planned for an evacuation of Stutthof, and they doubled the guard detachment, burnt incriminating documents and transported equipment away from the camp.

During 23-24 January 1945 the Russian army advanced close to Elblag and Malbork some 40 -50 kilometres from Stutthof. In view of this Gauleiter Albert Forster and the Higher – SS and Police Leader Fritz Katzmann decided to evacuate Stutthof, with the prisoners embarking on a “death march” to Lebork some 140 kilometres distant from Stutthof.

The formal order of evacuation was issued by Stutthof Camp commandant Paul Werner Hoppe, this order – Einsatzbefehl No 3 -was dated 25 January 1945, 0500 in the morning.

The evacuation which commenced at 0600 in the morning under the command of SS- Hauptsturmfuhrer Teodor Meyer, the march was expected to last seven days.

25,000 prisoners in nine columns started the march, the last two groups left on the 26 January 1945, in the morning, the conditions in which the evacuation took place has been described by prisoners who survived:

“How many of them fell down on the road, they were marching so long, until their legs could be pulled forward. When they fell down, a blow with the rifle butt tried to lift them up. They were too weak to continue the march, some of these falls were their last falls. An SS-man’s kick removed the body to the side of the road. Sometimes one kick was enough, or one knock with a rifle butt in the face, to finish the life.

We hardly passed Stegna, when one prisoner fell down, after that others were falling.”

The march actually lasted for ten days, not the seven days forecast, the Germans only issued food for two days, the sounds of artillery fire from the Red Army’s guns could be heard from the east and south. The columns marched on through snow drifts with the SS guards murdering anyone who fell behind.

After reaching Lebork the decimated columns of survivors dragged out a miserable existence till March 1945, when the Red Army liberated the survivors.

Those still left behind in the camp were evacuated on Himmler’s orders of the 14 April 1945, the only route open to the Germans was by sea. Many small scale evacuations by sea then took place.

The evacuation of the main camp together with the Gdynia sub-camps took place by sea to Hamburg, Flensburg and Neustadt on 25 April 1945, there were approximately 5,000 prisoners in five old barges, only about half this number survived the evacuations.

Following the main evacuations by sea, the camp practically ceased to exist, only about 100 -150 prisoners were left behind. The remaining SS-guards started the final liquidation of the camp.

The Jewish barracks were sent on fire, in which some sick prisoners were still inside, and so burnt alive, the SS men under the command of Paul Ehle left the camp, which was then taken over by the German army. Stutthof was liberated by Red Army soldiers of the 48th Army under the command of colonel S.C. Cyplenkow.

A number of war crimes trials were held after the war, the first commandant of Stutthof Max Pauly was tried by a British court for his crimes at Neuengamme concentration camp, and executed.

The second commandant of Stutthof Paul Werner Hoppe, who succeeded Max Pauly in September 1942, was initially given a sentence of 5 years and 3 months imprisonment, in Germany and this was increased to 9 years by a court of appeal.

In Poland during April and May 1946 more trials were held and death sentences were passed on 6 members of the camp personnel and 5 kapo’s, one caretaker received a five year prison sentence and a barrack supervisor a three year sentence. The death sentences were carried out on 4 June 1946.

The second trial in October 1947 saw death sentences passed on 9 members of the SS staff and one Kapo, including Jakob Meyer, Ewald Foth, Friedrich Rach, Paul Wellnitz. Other members of the camp’s staff received lesser sentences.

There were also several trials in Germany where a few of those found guilty were given small terms of imprisonment such as Fritz Selonke, the so-called “Butcher of Stutthof,” who received a two year prison sentence.

Otto Knott who had poured the zyklon B into the gas chamber was found not guilty in a trial in 1964 in Tubingen, Germany.

Sources:

Stutthof – Historic Guide by Tadeusz Skutnik, published by Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza 1980. Hitler’s Death Camps by Konnilyn Feig, published by Holmes and Meier, New York 1979. Stutthof Museum Guide by Romuald Drynko, Sztutowo 1993. The Camp Men by French L. MacLean. Weiner Library NARA.

Copyright: Chris Webb & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2007

|