Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Revolt & Resistance

Acts of Resistance

Jewish Resistance

Groups Jewish Resistors Allied Reports Anti-Nazi Resistance Nazi collaborators

| |||||

Malka & Edek Galinski Escape attempt from Auschwitz–Birkenau

Malka Zimetbaum was the youngest of five children born to Pinkas Zimetbaum and his wife Chaya, in Brzesko, Poland on the 26 January 1918.

The family moved to Belgium and Malka was registered as living in the city of Antwerp on the 21 March 1928. Malka was a model pupil and she excelled in mathematics and languages. She had a command of Flemish, French, German, Polish and English.

As an adolescent Malka joined Hanoar Hatzioni, a Jewish youth organisation in Antwerp and from this time she now preferred to be called Mala. To support her father who had become blind, Mala took a job as a seamstress for Maison Lilian, a major Antwerp fashion house.

Subsequently she worked as a linguist-secretary in a small company in the diamond trade based in Antwerp. Two years after the German occupation of Belgium Mala was arrested on the 22 July 1942, at Antwerp Central Station, on her way back from Brussels, where she had been looking for a hiding place for her family and herself.

The Germans took Mala first to the notorious Fort Breendonk, then five days later she was transferred to Mechelen, where German authorities had turned the Dossin Barracks into a collection and deportation point for Jews. Mala worked in the registry.

On the 15 September 1942, the tenth deportation train left the Dossin Barracks destined for the East, on board were 1048 deportees, including Malka. After a nightmare journey lasting two days Mala was subjected to the normal selection at the Juden Rampe outside Birkenau. Mala was one of the 101 females considered fit for labour, whilst 717 were gassed immediately.

She was placed in the women’s camp at Birkenau and after undergoing the normal humiliations for new arrivals at Auschwitz-Birkenau, was tattooed on her forearm with the number 19880.

Housed in a wooden barrack, originally designed as a horse stable and because of her skill with languages, she was employed in the camp administration as a Lauferin, whose duties were as a messenger and interpreter.

According to a fellow prisoner, “These girls had to stand next to the guardhouse waiting for orders. Whenever Camp supervisor Mandel or overseer Margot Drechsler needed them they yelled “Lauferin, and the girl had to do as ordered on the double.”

A prisoner called Raya Kagan who knew Mala in Birkenau, described her as such:

“I had known Malka since the summer of 1942. At that time she became a Lauferin – a messenger between blocks and a liaison between the Blockfuerherstube, the Kapo and the prisoners.

She was a young girl, of Polish origin, but she had been living in Belgium and arrived with the Belgian transport. She was very decent, she was known throughout the camp, since she helped everybody.

And her opportunities and the power, as it were, that she possessed were never wrongfully exploited by her, as was often done by the Kapo’s. She suffered like everybody else. However, she had better conditions – she was able to take a shower in Birkenau.”

Another Birkenau survivor Anna Palarczyk recalled after the war that:

“In my opinion, resistance in Birkenau was to help each other survive and Mala was eager to help, that was deeply rooted in her ethics. Mala fed starving prisoners.

Now and then Mala brought me some bread, a little honey, a carrot. Without that I would have died. She used to encourage desperate persons. Having recovered from typhoid fever, I had no shoes, I was really skinny. It was Mala who scolded me, “Take care of yourself! Get decent clothing. You’ve got to wash somehow.”

Mala even managed to send cryptic warnings to her family back in Belgium. The Camp authorities wanted to dispel rumours of extermination of the deportees and also arrest Jews who had so far avoided capture and allowed prisoners to write home.

Mala sent a postcard dated 25 August 1943 to one of her elder sisters, it read:

“Don’t worry. I am in good health, working as an interpreter. All the others are together with Etush.”

*It should be noted this was a clever warning as Etush, Mala’s sister-in-law had died before the war.

Another postcard written by Mala, dated the 25 October 1943 read:

“My dear sister, why don’t you write me? You know that every couple of lines from you will renew my courage to face life. Where are our dear parents, why don’t they correspond? What about the dear children? Thinking of it will drive me mad”

Mala’s fears were justified- her parents and her three nephews, aged 3,5 and 6 had been murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Mala formed a relationship with a Polish prisoner Edek Galinski, who was a veteran of Auschwitz, bearing the low tattoo number 531, who had arrived in Auschwitz in June 1940 from the prison in Tarnow.

Another prisoner who arrived at Auschwitz with Edek Galinski was Wieslaw Kielar who was a close friend of Edek recalled in the spring of 1944:

“Edek began to talk about his relationship with Mala, which had been developing for some time. I was surprised because up to now he had been so discreet and he usually avoided the subject.

At any rate, he had never before opened his heart to the extent which he did now. He had known her a long time, he said, he was very attached to her. They were living together and linked very closely, he found it difficult to part with her, particularly since she suffered from malaria.

He could not bear the mere thought that sooner or later she would have to share the fate of all the Jews. Now everything is fine, she’s even a favourite of Drechsler, everybody likes her. But when the moment comes, she will be the first to be sent to the gas chamber by Drechsler.”

Edek, Wieslar planned to escape, and Edek wanted the escape to include Mala, but although Wieslar at first agreed to it, he had serious reservations that Mala, who had not been well, and was Jewish could jeopardise their chances of a successful escape.

Edek brought Wieslar a portrait of Mala drawn in chalk to dispel his fears, over any pronounced Semitic features; Wieslar described her as having “a sweet and pretty face.” The portrait had been drawn by female prisoner Zofja Stepien.

Edek managed to obtain from his former Kommandofuhrer Lubusch an SS uniform, which he had left in a hut and had even found an SS guards identity card on the ramp, the date for the escape of all three of them were fixed.

On the eve of the planned escape Wieslar Kielar proposed a new plan whereby Edek and Mala escaped on the Saturday as planned, and that Wieslar would escape with another prisoner called Jozek on the Monday.

The uniform would have to be smuggled back to Birkenau in order for the escape to be repeated in the same manner, from the village of Kozy, objections and doubts remained, but this was agreed between Edek and Wieslar.

The escape took place on Saturday the 24 June 1944 around noon, with Edek dressed as an SS guard and Mala dressed as a male prisoner carrying a heavy lavatory pan.

Wieslar Kielar described the escape attempt:

“At last they were coming. Stocky Jurek side by side with a short figure in overalls, carrying a heavy lavatory pan, Mala was already bending down under this load. I gave a sign to Edek. He had been waiting for it because moments later he emerged from the bunker.

Brushing some invisible dust from his Rottenfuhrer’s uniform, he approached the side of the road and waited for the others to reach him. Jurek stopped in front of the SS man at regulation distance, executed a regulation about face and marched back.

Mala stayed behind with Edek. He let Mala walk ahead, while he moved a few steps behind her, casual, normal, as one would often see an SS man escorting a prisoner. Slowly they left the camp. I followed them with my eyes for a good three hundred yards until I lost sight of them because the road turned slightly to the right and disappeared behind the building of the potato bunker.”

At night at the Roll Calls in the men’s and women’s camp the sirens wailed, first in the men’s camp then in the women’s camp, as the SS discovered that two prisoners were missing.

Shortly afterwards the news spread through the camp like wildfire, that Edek and Mala had escaped. First Protective Custody Commander for the Men’s Camp Schwarzhuber was reported to have said, “that if such an old prisoner had got away, it wasn’t worth the trouble looking for him.”

Freedom however, was not to last. Both Edek and Mala are captured on the 6 July 1944 by the Bielitz Gestapo, and are returned to Auschwitz the next day, and are locked in Bunker II and subjected to brutal interrogations by the Political Department, after initially being treated kindly, which was unexpected.

Within the camp rumours were fife about how they were captured, Wieslar Kielar received a letter, better known as stiffs, in camp parlance, from Edek himself, which explained exactly what had happened.

The letter read:

“They were arrested in the Zywiek Mountains where they had run into a border patrol. They were taken to Bielsko and put in jail without being recognised because Edek continued to wear the SS uniform.”

The interrogations became more brutal they beat Edek’s bare feet with a metal rod, Mala too, was no longer handled with kid gloves. Wilhem Boger was in charge of the interrogations.

But despite the brutal treatment neither Edek nor Mala betrayed anyone, and the case was referred to Breslau for a ruling. The sentence was handed down, both were to be hung. Edek made another attempt at communication and stated that “Mala or himself would go to the executioner alive.”

Wieslar describes Edek’s execution, which took place on the 15 September 1944, Mala was also executed on the same day:

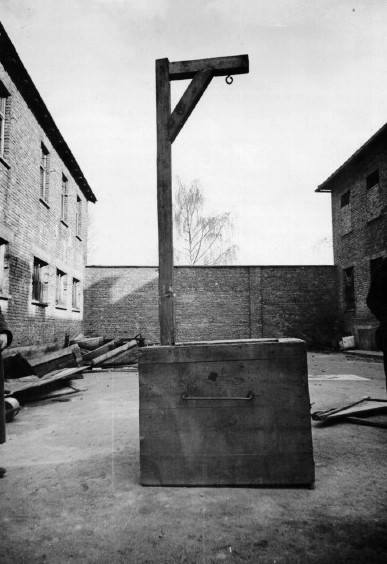

“Roll call was coming to an end. Now, as was customary on these occasions all of us went to where the gallows stood and formed a large square around the gallows.

I stood as near as possible to the small room from which Edek would be led to his doom. After a while the door opened and Edek appeared. There was complete silence. All that could be heard was the crunching of gravel under the boots of Edek, the condemned man, walking towards the gallows, and Jupp the executioner.

Near the spot where I stood people made way to let the two men pass. I squeezed myself into the front row, hoping that Edek would see me. He walked very tall, pale, his face slightly bloated. His eyes scanned the crowd for faces he knew.

I was sure he wanted to see me. I stood there, he almost touched me as he went past. A whisper would have been enough, “Edek” – but at that moment I was not capable of even that. I stood as if paralysed. Edek went past me without noticing me.

Now I saw his straight back and his hands drawn behind his back and bound with wire. Bravely Edek mounted the scaffold and immediately climbed onto the stool that had been placed beneath the gallows. The noose touched his head.

The command “Attention” was given. After a while an SS man silently stepped forward and read out the sentence in German. At this moment Edek standing on the stool sought the opening of the noose with his head – then he vigorously kicked away the stool and hung. He kept his word - he would not deliver himself alive to the hangman.

But the SS men would not permit such a demonstration. They began to shout and the Camp Kapo understood them at once. Grasping Edek round the middle, he placed him back on the stool and loosened the noose.

The German finished reading the sentence in German and begun muddling it in Polish. He read fast and unintelligently. He was in a hurry. Edek waited until he finished. In a moment of utter silence he suddenly cried in a choking voice, “Long live Poland –“he broke off in the middle of a word. Quickly Jupp drew away the stool, and this time the noose was pulled tight.

Edek’s body tightened, twitched and then remained hanging limply, his head dropped to one side. He was no longer alive.”

There are various versions as to how Mala’s died in Birkenau, the complete truth may never be known, but various eyewitness testimonies have stated the following.

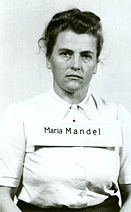

“After evening roll call, the female prisoners were ordered to form a circle near Block 4 in the women’s camp Blb. The Lagerfuhrein Maria Mandel and overseer Margot Dreshel and several SS guards were also present when Mala was brought forward by SS Unterscharfuhrer Ruiters, towards the gallows.

While Lagerfuhrein Maria Mandel read out the sentence, Mala slashed her wrist with a razor blade. As blood poured from the wound Ruiters tried to grab the blade, but Mala hit him, which was the trigger that made the SS beat her severely, breaking her hand in an attempt to seize the razor blade.”

Mala was then put onto a handcart and taken to the Crematorium, where some sources say she died on the way. Other sources claim she was shot by the SS or was thrown into the crematoria alive. Mala though like Edek had kept her promise, she had not been taken alive by the executioner.

Mala Zimetbaums story was made available to the public in the official testimony of Mrs. Raya Kagan, delivered on June 8, 1961, during Session 70 in the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Mala is still remembered even to this day, and many Auschwitz survivors regularly gather to pay their respect to this brave woman, and a plaque has been placed on the house where her family lived in in Antwerp, scholarships and even a B'nai B'rith lodge have been named in her honor. Sources: Anus Mundi – Five Years in Auschwitz by Wieslar Kielar published by Penguin Books 1982. Kulka, Erich, “Five Escapes from Auschwitz,” in They Fought Back, op. The Auschwitz Chronicle – Danuta Czech published by Henry Holt New York 1990. Mala – A Fragment of a Life by Lorenz Sichelschmidt. Adolf Eichmann Trial Transcripts – Nizkor

Copyright Victor Smart & Ryan Harrison H.E.A.R.T 2009

|